Wild Florida attracts millions of visitors each year from around the world. Whether it’s relaxing on sandy beaches, diving into clear springs, or searching for animals only found in the Sunshine State, there is something for everyone to fall in love with. Many visitors are inspired by the state’s natural wonders to donate to the Foundation to conserve it for future generations. Here are some of their stories.

Love from Australia (via North Carolina)

Caroline Makepeace moved with her husband Craig to North Carolina in 2004 to teach elementary school and explore the country. The Tar Heel State made a lasting impression on them, but after four years they returned to their native Australia. While Down Under, their mutual love of travel led to the launch of their Y Travel blog. The blog’s success afforded them the option to live anywhere, and in 2017, they decided to make Raleigh their new home.

Caroline Makepeace moved with her husband Craig to North Carolina in 2004 to teach elementary school and explore the country. The Tar Heel State made a lasting impression on them, but after four years they returned to their native Australia. While Down Under, their mutual love of travel led to the launch of their Y Travel blog. The blog’s success afforded them the option to live anywhere, and in 2017, they decided to make Raleigh their new home.

However, moving to America did not mean becoming homebodies. The family dove into exploring every corner of the country. They lived in a RV for a year, roaming around the West Coast until October 2019. The pandemic has limited their recent adventures to locations within driving distance and the ability to socially distance while enjoying the sites. These needs led the Makepeace family to visit northern Florida in early July 2020.

They were tipped off to the natural, and often overlooked, wonders in north Florida through conversations with Visit Florida. Caroline, Craig, and their two kids explored the area for eight days, swimming in Madison Blue Spring State Park, scalloping in Steinhatchee, strolling through Live Oak and Monticello, and relaxing on Cedar Key. “It was the perfect getaway for this summer,” said Caroline. “We were able to be remote while adventuring in nature. We socially distanced while having brand new experiences, like scalloping.”

Caroline and Craig donated to the Foundation as a fundamental component to their trip: they believe their travels should also benefit local organizations that support the community and environment they enjoyed.

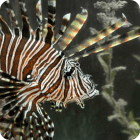

Supporting the Reefs from Across an Ocean

Andreas Wagner and his family started visiting Florida 20 years ago from Bavaria. They particularly enjoyed fishing, marveling at the abundance of life in the state’s waters. Andreas was struck by big predators like alligators and bull sharks that are not found in Europe. The wilds of the state hooked them, and they continued to return year after year.

Andreas Wagner and his family started visiting Florida 20 years ago from Bavaria. They particularly enjoyed fishing, marveling at the abundance of life in the state’s waters. Andreas was struck by big predators like alligators and bull sharks that are not found in Europe. The wilds of the state hooked them, and they continued to return year after year.

Andreas became a donor to the Foundation’s Restoring Our Reefs campaign to protect the natural wonders in our waters, especially the reefs. The Florida Reef Tract is the cornerstone of biodiversity and health in our oceans, and Andreas is committed to supporting their restoration. “Florida has many things to offer, but the main attraction for me are the reefs, the mangroves, the sea grass flats, and all the animals that are living there,” he said. “Without them, Florida is another warm and sunny place to spend the winter, but nothing special.”

Florida Birds Find a Friend in Nebraska

Bill Cita has been an environmentalist for decades. He always cared about the plight of endangered species, but in 1982 he became particularly interested in the cranes making a pit stop near his home in eastern Nebraska on their annual migration. In fact, Bill was an early supporter of the Audubon Society’s Rowe Sanctuary. The Rowe Sanctuary in Gibbon, NE is front row viewing for one of the last great wildlife migrations on the planet. Being in the heart of a critical spring staging area for sandhill cranes, Bill developed a love of the bird so often associated with the Sunshine State.

Bill Cita has been an environmentalist for decades. He always cared about the plight of endangered species, but in 1982 he became particularly interested in the cranes making a pit stop near his home in eastern Nebraska on their annual migration. In fact, Bill was an early supporter of the Audubon Society’s Rowe Sanctuary. The Rowe Sanctuary in Gibbon, NE is front row viewing for one of the last great wildlife migrations on the planet. Being in the heart of a critical spring staging area for sandhill cranes, Bill developed a love of the bird so often associated with the Sunshine State.

When Bill saw that another Florida bird, the Florida grasshopper sparrow, was in danger of going extinct, he was quick to act. “I couldn’t live with myself if I did nothing, even though their situation seemed hopeless,” Bill said. “I’m in it for the long haul.” Fewer than 40 nesting pairs remained in the wild, making the Florida grasshopper sparrow North America’s most endangered bird. Habitat fragmentation and loss due to development, lack of frequent prairie fires, storm-related flooding, and predation have caused a dramatic decline in its population over the past 40 years.

But our work, with Bill’s help, is reversing the tide. The first of the captive-reared sparrows began being released back into the wild in May 2019, in hope of stabilizing and growing the largest-remaining wild population of the birds. More than 50 birds were released in 2019, with another 106 planned to be released in 2020. As of August 2020 biologists have observed 22 released males and nine released females. Pairs with at least one captive-reared bird have had 21 nests, 15 of which have fledged young. So far, 42 fledglings have been produced by pairs with at least one captive-reared bird. In answering the call for help for four straight years, Bill has provided consistent support for this work, helping to ensure the sustainability for the program and an optimistic future for a bird once on the brink of extinction.

Join these supporters today to add your story to Florida conservation’s history.