By: Nicole Forsgren

Although red tide outbreaks are a natural occurrence, their pervasive nature is troubling. Research is still in the beginning stages, but it has been determined that early detection, along with persistent monitoring of the blooms and a better understanding of environmental factors, may allow the possibility of a safer tomorrow.

Karenia brevis is considered to be the root of red tide proliferation. This marine dinoflagellate (a single-celled protist) is responsible for the production of toxins that lead to the demise of marine life. Marine algal bloom growth has a negative impact on the marine life, water quality, and humans alike. In addition, tremendous amounts of annual revenue are lost in the areas of fishing and tourism due to the red tide devastation.

In addition to the production of early detection instruments, Mote Marine Aquarium has proposed some methods for the alleviation of red tide. These ideas include the use of ozone, filter-feeders, macro-algae, and parasites. By introducing competition, K. brevis may fail to spread. In the ongoing battle to reduce red tide triggers, any and all methods are possible.

Due to the severity of the current red tide outbreak, residents all over the state of Florida share a common concern; is there something people can do to help? To better understand this endemic, we caught up with Dr. Leanne Flewelling- a research administrator at the Fish and Wildlife Research Institute’s red tide research and monitoring program.

FWFF: Although red tide outbreaks are considered to be a natural occurrence, what contributes to the abundant outbreak of red tide? Have humans negatively contributed to this ever-growing endemic?

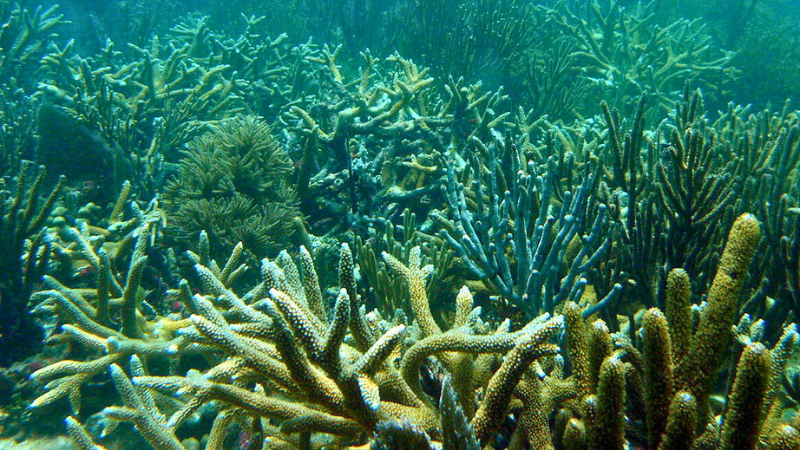

LF: Blooms of Karenia brevis (the organism that forms red tides in the Gulf of Mexico) are a natural occurrence that has been reported in the region for centuries. Red tide blooms are complex phenomena that result from the right combination of biology, chemistry, and physics. Blooms begin offshore, using nutrients upwelled from the deep ocean or regenerated from other algae, but once they move inshore, K. brevis can use any available nutrients, whether naturally occurring or man-made. In that way, humans may be providing nutrients to fuel nearshore or inshore red tides. The physics are very important too – the current red tide has remained inshore much longer than most past events due to prevailing winds and currents.

What environmental conditions lead to the consistent outbreak in Southwest Florida around the same time, each year?

Historically, K. brevis blooms usually begin in September or October, but they have occurred in all months. We believe blooms initiate offshore in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico and are transported inshore with upwelling and winds. Seasonal changes in upwelling conditions and prevailing currents result in bloom transport to the Southwest Florida coast in late summer or early autumn.

How are water quality, humans, and marine life affected by red tide outbreaks?

Severe K. brevis blooms can temporarily cause low dissolved oxygen – like any dense algal bloom can.

Filter-feeding bivalves ingest K. brevis cells during blooms and they concentrate toxins, called brevetoxins in their tissues. Brevetoxins are neurotoxins, and ingestion of contaminated shellfish by humans can lead to Neurotoxic Shellfish Poisoning. This is why shellfish harvest is banned in areas where red tides are occurring. The toxins are also aerosolized by waves and carried on shore by winds, and they can cause respiratory irritation in humans who inhale the toxins. For most people, the symptoms go away as soon as they leave the beach, but more severe symptoms are possible in sensitive people – like infants or elderly people – and in individuals with pre-existing lung disease, such as asthma.

Of all the different types of harmful algae in the world, I think that K. brevis red tides affect the most diverse array of aquatic organisms. The toxins are very deadly to fish, which is why we have such massive fish kills during severe red tides. They can also accumulate in the food web and lead to illness or death of sea birds, sea turtles, and marine mammals.

What kind of efforts are being put forth by the FWC to control red tide?

Given the scale of red tides, which can cover thousands of square miles, controlling these blooms is probably impossible. Approaches for dealing with red tide in localized areas, like canals or small bays, might be feasible. At FWC, small-scale studies looking at natural grazers to control harmful algal blooms are underway but are in early stages. Other researchers are looking at other biological or chemical approaches to controlling K. brevis blooms, but the challenge is to find an environmentally acceptable method that specifically targets K. brevis without causing widespread mortality of other organisms by direct harm or through release of toxins from dying K. brevis.

Our primary focus is on mitigating the negative impacts of red tide by providing information to the public and to resource managers. We provide technical support to the Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services, the agency that regulates shellfish harvest, and information on bloom status and short-term projections of bloom movement to both resource managers and the public. Knowledge is power! A lot of our current research is focused on ways to improve red tide monitoring and detection of red tides in the early stages, which can help inform models being developed for red tide predictions.

What biological and/or chemical factors have proven most effective in controlling these outbreaks?

None, really. Researchers have found several ways to kill K. brevis, but they have yet to demonstrate an approach that doesn’t cause other ecological harm. Also given the scale of the blooms and the dynamic environment they occur in, cells are likely to move back into a treated area pretty quickly. Effectively treating even a small canal would be challenging.

How does red tide differ from blue-green algae?

K. brevis is a type of algae called a dinoflagellate. Blue-green algae are cyanobacteria, which is a different type of algae. There are both marine and freshwater species of dinoflagellates and cyanobacteria, but K. brevis is strictly a saltwater species and the blue-green algal blooms in Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries are freshwater species that can only tolerate low salinities (<18).

Can the loss of marine life be attributed to the biotoxins that are produced by these algal blooms?

Yes, brevetoxins are the main cause of fish and wildlife mortalities during red tides.

What are the financial ramifications of a red tide outbreak?

Economic consequences of a bad red tide are diverse and can be significant, easily leading to millions of dollars lost in revenues for commercial fisheries and aquaculture as well as recreational and tourism. Because of the magnitude of dead fish associated with this year’s bloom, state and local governments are also spending thousands of dollars each day on beach clean-up efforts.

How can people help? Can early detection prevent such severe outbreaks?

People can help by reporting fish kills to the FWC Fish Kill Hotline: myfwc.com/fishkill

We also have a network of volunteers that assist with water sampling:

myfwc.com/research/redtide/monitoring/current/offshore-monitoring/

Early detection can help minimize negative effects by providing time to prepare for the bloom coming inshore, but there is currently no mechanism to control a red tide. Efforts that minimize nutrient loading into estuaries (like adhering to local fertilizer bans in the wet season) may reduce the food available to sustain the blooms, but there are multiple sources of nutrients in nearshore waters, and while this might help to reduce the severity of the blooms, we will still have red tides.